Articles

When flying at competitions, or just going cross-country, a tow/retrieve driver is a crucial part of your team. This is why it is extremely important to show appreciation and respect toward your driver. Without these volunteers, you could be sleeping out with the mosquitoes and drop bears! In towing competitions, the tow driver literally has your life on the line. HG Comps Inc., as a collective, have decided to offer some guidelines to help you look after your driver and ensure we have a pool of happy, experienced and willing drivers into the future.

I have been a driver for the last 18 years, mainly for my partner Andy, a hang glider pilot of 27 years. My experiences have been mostly positive, except for the odd grumpy pilot (we’ll call him ‘Mr Grumpy’) who didn’t get picked up first when he thought he should! While most pilots and teams are respectful, drivers I have spoken with over the years found this unfortunately not always to be the case. Some have relayed stories of driving for teams where they have been verbally abused and generally disrespected, treated poorly and given abysmal reimbursements!

Back in 2007 when I started driving (I think I got tricked into it!), the share of reimbursement for a driver was $25 per pilot per day which I considered to be a reasonable token of appreciation at the time. We are now 18 years down the track and I hear some teams still reimburse at $25! Pilots are even trying to not reimburse their driver for ‘no fly’ days, which is not new, as I have had this happen many times. Remember that your volunteer driver is there to look after you, they are not on holiday, pilots shouldn’t expect volunteers to not get reimbursed on no fly days! Drivers actually hate the ‘no fly’ days as they have to wait around with a bunch of unhappy pilots. We would rather you’d be out there flying than sit there with us in the rain.

Many of our driver volunteers have well payed jobs in the ‘real world’, so they are not driving for you for money. Those who come to mind have the following occupations: barrister (not barista – if you don’t know the difference I can’t help you!), CEO, nurse, podiatrist and accountant. Some of these are also ex-pilots – do you begin to see their value? These people are giving up their own free time to drive for you. It is not a holiday for them, they are helping out as volunteers.

If you were sent on a job for a week out of town, you would expect to be reimbursed for your accommodation and meals. Volunteer drivers don’t expect the Taj Mahal or a Michelin star restaurants, although both would be nice! A spot on your campsite, a shared cabin, food and drink, a meal at the pub, and a salad roll for lunch all help to show your appreciation and respect for the time, effort and expertise they put in for you.

Making sure the car is full of fuel at the start of the day is another must! A driver (let’s call her Angela) recently told me that after a day of towing in the dusty Birchip tow paddock, she pulled out of the gate only to realise the team had left her just 20km worth of fuel. She then spent time looking for a service station to fill up, using her own money, when she could have been on the road to pick up pilots. Roadside Assist is an awesome thing to have on your car as well, if the driver breaks down or runs out of fuel, they can call the RACV or equivalent for help. The quicker they get back on the road the sooner you get picked up!

To give a general idea of what transport costs for other sports, Perisher (Kosciuszko National Park) snow-skiing lift passes for one adult will set you back $202 per day, and mountain bike shuttles in Derby, Tasmania, cost $145 per person for two days. Considering this, each pilot’s share for reimbursing their drivers are rather more reasonable. While volunteers are not being paid, they should not be left out of pocket for their efforts to help make your lives easier. Volunteer drivers are an integral part of the team, we should treat them with respect and show our appreciation by paying appropriate reimbursements. If you want to shine in the eyes of your driver, purchase them a comp T-shirt, so they remember you next time you ask for help.

When you do all these things, drivers will be happy to offer their help and you won’t be madly scrambling to find someone at the last minute. For guidance on what we think are appropriate reimbursements, see our Guidelines at HG Comps.com. And keep hang gliding awesome!

Managing tow/retrive driver & vehicle expenses - January 2025

Volunteer drivers are an intergral part of your flying team. Treat them well and reimburse them appropriately.

Retrieve vehicles owners also often get a poor deal from their team mates, don't let this happen!

All team expenses should be shared equally by all team pilots.

Driver Expenses

- Accommodation

- Driver Meals / Drinks

- Daily reimbursement rate (inc. “No Fly” days – don’t be a tight ass)

- Hill launch - $30 - $50 per pilot / day

- Car tow - $40 - $60 per pilot / day

Vehicle Expenses

Is your team just paying for fuel and letting the vehicle owner bear these other costs?

- Fuel

- Cleaning

- Maintenance

- Depreciation

- Insurance

- Breakdown / Damage

OR

- $1 (minimum) per km travelled method: All team pilots pay an equal share of logged distance travelled by vehicle to its owner who covers all vehicle expenses.

Tips for a happy driver & team

- Fill up the fuel at the start of the day (don't leave your driver with an empty tank)

- Cash or card in car for driver to refill fuel or eski

- Water + lunch in the car for driver

- Road side assist recommended

- “Group Xpense – track & Split” App – tracks team expenses.

Have a remuneration agreement before you engage your driver / vehicle to help prevent future disappointment.

Consider driver experience at the type (hill vs tow) and location of competition when offering daily reimbursement rate.

Consider how much you would want to be reimbursed if you had to drive instead of fly.

We need drivers to enjoy all aspects the competition experience so that they want to return next year.

#hangglidingisawesome

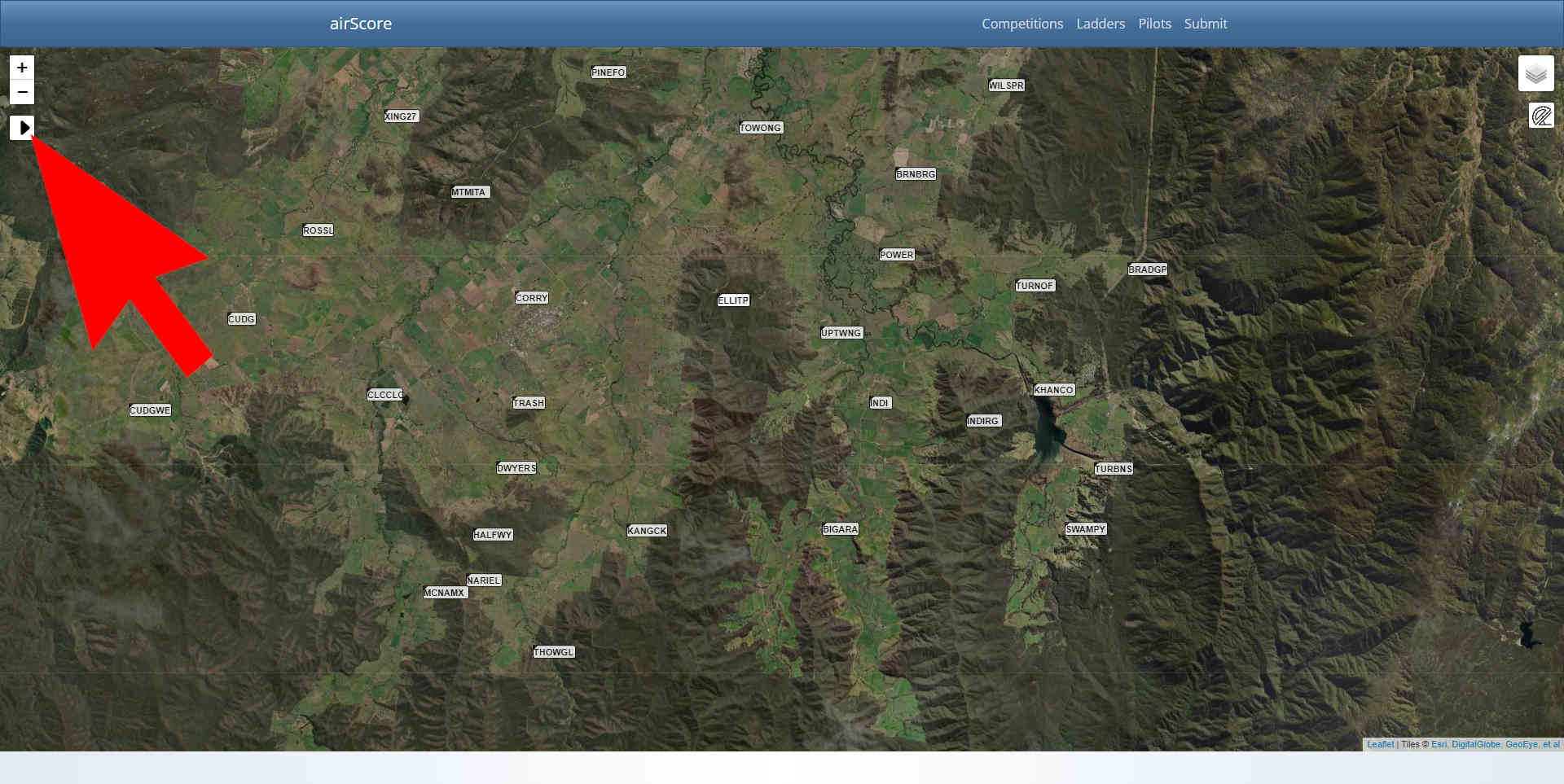

How to download waypoints from the AirScore site.

scroll to bottom of page for links

If a competition is to be scored on AirScore (xc.highcloud.net) then that is where you should source your waypoints.

By doing this you can ensure that you are using the same waypoints that the scorer is using.

There are links to waypoint sets at the bottom of the page.

The link will take you to a map page showing the waypoints.

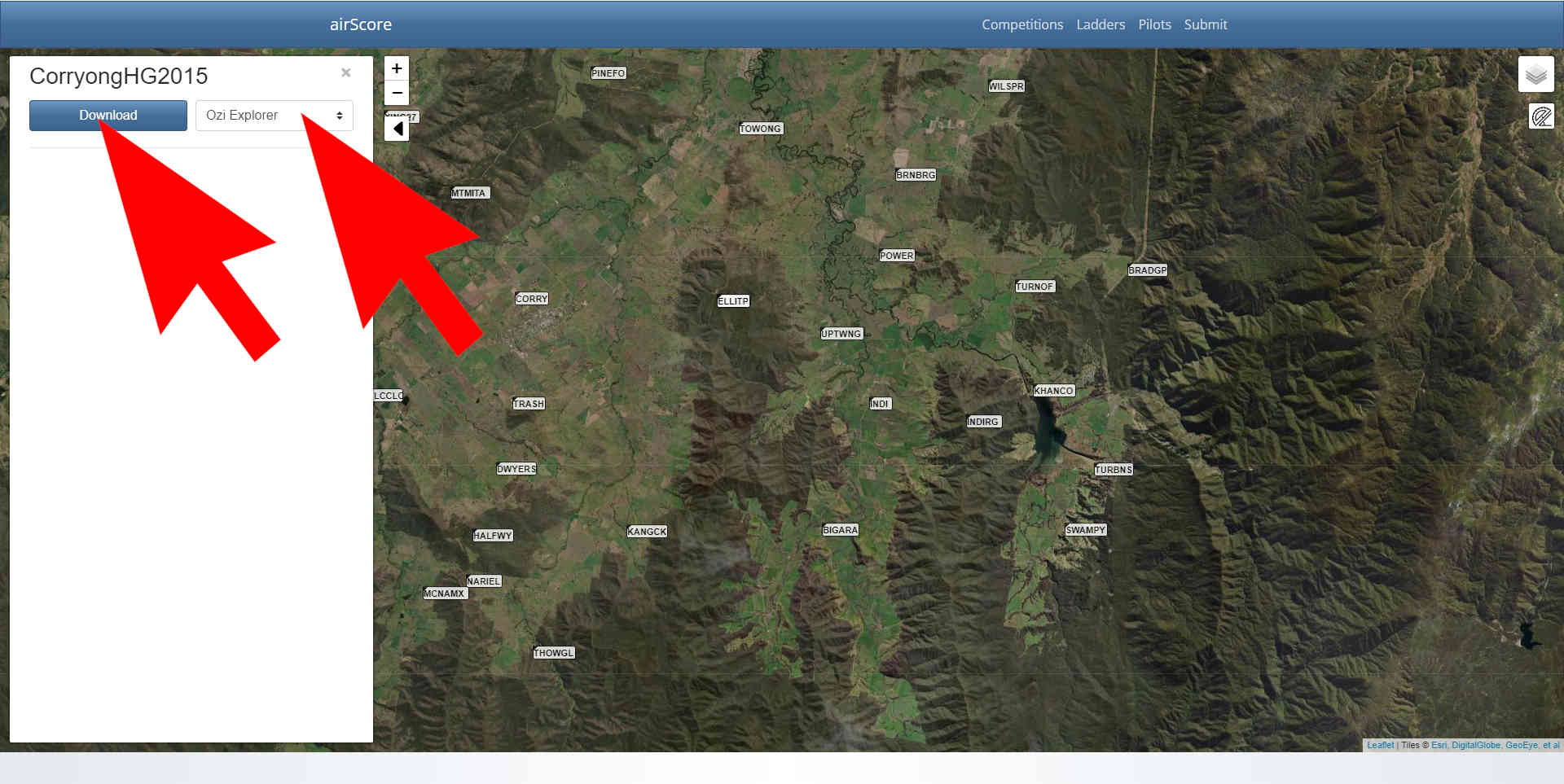

Click the arrow on the far left.

A download panel will open showing the name of the waypoint set.

Choose the appropriate format for your navigation instrument.

OziExplorer; CompeGPS; SeeYou (.cup); or UTM

Click the download button.

Import into your navigation software from your downloads folder.

Click here --> CorryongHG2015 for the waypoints used at the Corryong Cup

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Click here --> Birchip2022 for the waypoints used at the Flatter Then The Flatlands

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

To select waypoints for a different competition go to

https://xc.highcloud.net/comp_overview.html

and use the search box to find and open your competition.

On the next page look in the masthead banner for a 'Waypoints" button and click it.

Now follow the instruction from the top of this page.

You must ensure that you are downloading the correct waypoints set for your competition.

XC Tactics for pilots new to competition

Hang gliding competitions are a great environment to learn and improve your flying skills. If you are a new pilot coming to your first competition it can be daunting. All of a sudden you are in the mix with a lot more pilots than you have ever seen in one place before. You may worry that you don't have the skills to compete or will be getting in the way of others when in the air. Don't be concerned. Hang glider pilots are generally very accepting and helpful toward new pilots.

We are all very different people with different levels of comfort with risk. while I am not suggesting that risk taking is synonymous with hang gliding, it would seem that some top level pilots are doing things in the air that I would consider too risky for me. It is very probable that this is due to their greater flying competancy & currency and not risk taking behavior. The point that I am trying to make is that if it feels like a risk to you, don't do it. If you are scared while you are flying then you are not enjoying yourself, this will not help with your skills progression. Don't ever be trying to fly beyond your current abilities. Learning new skills takes time & practice. If you are flying a competition task and it feels 'risky', then you can alway backtrack to the 'fun zone' and either continue flying, or land. There will always be another flying opportunity tomorrow.

This article contains some tips & have learnt or read myself over my 25+ years of flying and 'competing'. It is not intended to be a complete guide to cross country flying. Just an entry level primer to give newer pilots some things to focus on to extend their abilities. For those newer pilots at a competition you should not be trying to 'compete' or be trying to fly fast. Initially you should focus on learning how to navigate a task, read the sky and the ground, be safe and try to stay in the air long enough to get to goal. If you can do this every day then you are well on your way to the podium at the end of the competition. You may pick & choose what you want from this article, different things work for different people. The main thing to remember is that you don't have to work it all out for yourself. There is an abundance of pilots out there who will share their knowledge and experience if you ask them.

If this is your first competition, one of the first problems you may need to overcome is leaving the comfort & security of the hill. To be able to compete at an XC competition you must be prepared to 'land-out'. This means you have to have a handle on things such as:

- Indicators of the ground wind speed & direction: wind lines on dams, trees bending in the breeze, smoke & raised dust, glider drift when circling.

- Terrain slope direction. Mountains are easy, valleys usually slope down toward rivers, creeks & dams. Solid white dividing lines on straight roads can indicate a crest.

- Location of power lines. These can be invisible until it's too late. Look for lines of power poles leading to any house, shed, pump shed, tank or dam. Poles can be hidden in trees, in cultivated paddocks you can usually see the poles surrounded by small islands of ground cover/weeds. Also expect every road to have power lines running parallel.

- Location of fences. These also can be invisible until you are on final. Suspect that any abrupt change in paddock colour is a fence.

- Which paddocks have crop in them. Please don't land in crops. If the paddock is uniformly green or golden with no harvester wheel tracks in it. Then it is in crop.

- Which paddocks have stock in them. Avoid landing anywhere near horses. Be wary landing in a paddock with only a few 'cows', it's probably the bull paddock. If landing with cows or sheep, maintain plenty of seperation to avoid startling them. We don't want them injured or running through fences. If possible pick another paddock.

- Whenever flying XC, every few minutes scan the ground ahead on course to always have more than one landing option. Also be looking for thermal sources so you wont need to land.

There is a gread video presentation by Vic Hare & Jon Durand that is well worth watching here: Vic & Jonny on starting out XC flying

If you are comfortable in leaving the familiarity of the launch hill and the bombout then now you can focus on some tactics to extend your flight.

A successful flying task starts way before you launch off the hill. Remember the 5P's - Prior Preparation Prevents Poor Performance. There are many things that can be done to prepare you for the days flying. Some are obvious, some are not obvious.

- Know your flight instruments. Learn (on the ground) how to operate your vario/gps so that it is easy to use in the air. Distractions lead to poor decision making and poor flying. Don't be that pilot flying blindly in the gaggle because you are focused on your navigation display.

- The night before make sure instruments and radio are charged and working correctly. Make sure your team has access to backup gear or batteries on launch.

- Look after your nutrition & hydration. Both are required for good brain function & the physical exertion that will be required. Keep drinking water throughout the morning and have an easy to use in-flight drinking system. If drinking makes you pee, learn how to do this while flying. This is a game changer for longer flights.

- Get up to launch with plenty of time to spare so you can be completely set-up & relaxed by the time the task briefing is called. If you are late and rushed you may forget/skip parts of your normal setup procedure. This can lead to apprehension, agitation, or distraction that may see you land-out early.

- Pay attention at the morning weather briefing and task breifing. Make sure your navigation instruments have the task correctly programmed. Get help if you need it but even better learn and practice before you get to the competition. Have a look at the task on a map and come up with a plan of how you can use the terrain to your advantage while flying - discuss this with more experienced pilots if you like. Another idea is to write the task with a diagram on some tape stuck to your basebar. This can be useful if your navigation instrument is less than helpful at turnpoints. Or if you are flying without navigation instruments (you will still need to record a tracklog somehow for scoring).

- Watch the sky during and after setting up your glider. If it is looking soarable (birds are soaring or wind dummies are staying up), then launch early if the competition rules allow it. Launching early gives you the opportunity to fly with the better pilots. They will all catch-up and pass you at some point. If you watch them you will see where the lift ahead may be. Launching early also gives you the opportunity at a second try if you bomb-out. Also acknowledge that it will probably take you longer to fly the task than others so you will need more time in the air. Going later in your ordered launch position (based on pilot ranking) means more time waiting in the launch queue (and the heat).

So now you are well prepared mentally & physically. You have total confidence in all of your equipment and you have a plan as to how you will fly the task. You have made it to the front of the launch queue. You have been watching the launches ahead of you and are full of confidence because you have seen several gliders out in front circling-up.

- Stay relaxed on launch, integrate any advice from the launch marshal. The launch marshal is not there as an instructor, but you can certainly expect help holding you glider down in rowdy conditions and guidance on when a good launch cycle is approaching. Try to not lift your glider off the ground until you and the conditions are ready for launch. It's too stressful standing & holding your glider up in the wind. When you think you are ready pick up your glider and try to level the wings. If you can't get it settled and ready to launch in 5 seconds set it down again and wait.

- When launching remember how your instructor taught you. Smooth acceleration building to an excess of speed. Maintain proper pitch control and get the glider flying fast enough before it has to carry your weight off the launch.

- Once you have launched, get as high as you can before leaving the start circle. You want to start your race with a full tank of fuel. Don't be concerned with start gate times unless you are able to make goal consistently. Speed on course means nothing if you don't get to goal.

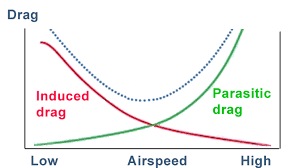

- Being fast is not aways about flying fast. This is particulary true with lower perfomance gliders. Gliders become increasingly less efficient as you accelerate past 'best glide' speed. All non-lifting surfaces (top rigging, bottom rigging, control frame and pilot) create parasitic drag which increases at a rate preportional to the square of your velocity.

- Being fast means flying efficiently:

- While you are thermalling be constantly scanning the sky and ground.

- In the sky keep a lookout for other gliders that are a collision hazard; other gliders or birds that are climbing better than you; what is happening to the clouds ahead on course, are they building or decaying?

- On the ground be looking for landing options ahead on course, always have several; look for ground/terrain based thermal sources; look ahead to identify the turnpoint you are flying toward.

- My first rule for flying fast is don't do anything that is outside your comfort zone. You flying for fun, and to learn. It's OK to land if you're not 'in the zone'. Also If implementing any of the ideas below might put you on the ground then choose a different alternative.

- Leave your thermal when the lift drops off below what you expect to be the initial climb rate of your next thermal. Keep a 'mental model' of the average thermals you have encountered that day. Be aware that if lift drops-off at a lower than expected altitude then you may have lost the core in a wind shear layer and need to search for it again.

- Leave your thermal when you get to the top. Some thermals are continuous for most of the day, some go in cycles/bubbles. It is possible to climb in a thermal up to the rising bubble at the top. Once you hit the top generally the lift will slow down and the air gets lumpy. The thermal may try to push you out horizontally. Time to leave if you are racing, or stay and continue climbing slowly if you want to play it safe.

- Leave your thermal before you get to cloudbase. Once you are at cloudbase you risk getting 'sucked-in' and 'whiting out'. This can be extremely dangerous! Don't do this! Also once near cloudbase you can loose definition of individual clouds ahead on course (from your angle it looks like the entire sky is one cloud). This makes selection of the next cloud you want to fly to harder.

- When gliding between thermals fly at best glide speed. In a floater glider don't pull on too much speed as the drag/sink penalty is not worth it. The only time for excessive speed is when there are thermalling birds/gliders (that are climbing better than you) ahead within your gliders range and you have the height to get there quickly. Other uses for fast flying are when gliding for goal and you find youself embarassingly high, or if you need to traverse/escape a venturi wind effect in mountains.

- Be aware that 'lift lines' can sometimes exist parallell to the prevailing wind. Know what your gliders sink rate is and set you sink alarm accordingly. If you are gliding in sinking air then try turning across the prevailing wind until sink decreases to normal before resuming your turnpoint heading. You may even encounter lifting air that you can glide through straight into your next thermal. When your task heading is not directly downwind, it may be more efficient to fly lift lines and zig-zag your way toward the turnpoint. When turning crosswind always stay upwind of the turnpoint. You don't want to find yourself past the turnpoint (but not yet in the 400m radius) and having to fly headwind back to it.

- While you are thermalling be constantly scanning the sky and ground.

- While you are gliding toward a turnpoint aquaint yourself with the direction of the following turnpoint and which way you need to turn. Before you get to the turnpoint have some landing paddocks picked out for the next task leg. Then get a plan of action so you don't waste height after tagging the turnpoint. Look for any gliders thermalling nearby, Are there any promising looking clouds growing nearby or reliable ground thermal triggers? Do you have the height to tag the turnpoint first and the join the thermal or do you need to top-up first? Know beforehand where you are going as soon as you have tagged the turnpoint.

How many turnpoints you have to navigate will depend on the class of glider you are flying and the conditions on the day. Floater class will usually have it's own shorter task. Sport class will probably be flying the same task as the Open class. The number of turnpoints doesn't matter. Just fly one leg at a time, always be looking ahead for gliders, birds, dust, smoke, ground thermal souces. Use all of the data available to you to plan your route, but don't be in a rush. At 'beginner' level it's more important that you have an enjoyable, safe flight and maximise your time spent flying. Flying conservatively and staying in the air is going to teach you more than flying fast and landing 2km outside the start circle.

The trick is to have a plan, don't just bumble along making it up as you go. Have a plan and make decisions based on what you see and learn on each task. Some of those decisions, may turn out to be wrong, this is OK. In flight you are subconsciously making several decisions per minute. It usually takes several wrong decisions to put you on the ground. The more you can plan ahead and have options, the better decisions you will be able to make. Learning what works and integrating this data into future decisions is the goal.

After your flight each day rehydrate & refuel you body to be ready for tomorrow. Charge-up your radio & instruments if needed. You can also review the days flying using flight evaluation software. You can see what other pilots did in their flights that may have worked better than what you did.

HG team cars & drivers

Flying your hang glider is often a solitary endeavour. Many pilots, in particular those who fly on the coast may be able to launch and land within a short carry from their car and don't rely on others for a lift.

Once you start flying XC your intention is to land a significant distance from where you launched. This usually requires additional logistical planning to get you and your glider back home after the flight. There have been several solutions to this problem employed over the years, usually involving either hitch-hiking or leaving an alternate car at the proposed landing site. Sometimes when a bunch of pilots go weekend flying together they may leave logistical planning to whomever lands closest to the car.

All of these solutions may be OK for a weekend fly but when you go to a competition and may have to repeat this process 7 days in a row it can become tiresome especially if you are the one who ends up doing all the driving.

Hang Gliding competitions are great learning environments. The best way to learn a new skill is to hang out with, those who do it better than you. This is very true in hang gliding. If you haven't done any competitions before try to get on a team with more experienced pilots. Then you can spend all the time in the team car integrating great flying tips & cool vibes..

When competing in a hang gliding competition a good driver will be an integral part of your team, in particular at a car towing competition. Driving at a hang gliding competition is a job. You will have to pay you driver. Your team should negotiate the fee with the driver before engaging them. If you are wondering how much to pay your driver then consider what you would like to be paid per day then divide that by the number of pilots on your team. $30-$50 per pilot per day is a reasonable amount. If it is a car-tow competition the drivers workload and stress is increased, expect to pay more. Experienced car-tow drivers are priceless. Pro-tip: Drivers perform better when well fed. Take turns with your team mates buying them a meal each night.

You will also have to pay to owner of the vehicle a share for fuel, depreciation and cleaning. Most teams will split fuel bills, this may be fair if the vehicle owner doesn't pay a share.

Another system is to have the entire team pay a rate per km. This involves running a vehicle log to record distance travelled. All pilots contribute equally to pay the vehicle owner eg: $1/km and the vehicle owner covers the cost of fuel, maintenance, depreciation & cleaning.

It is up to your team to decide how these costs are covered but again I suggest you decide this in advance so that everyone knows their expected costs and agrees. If a member of your team thinks that the proposed costs are too high, then simply suggest the teams uses their car with the same fee schedule.

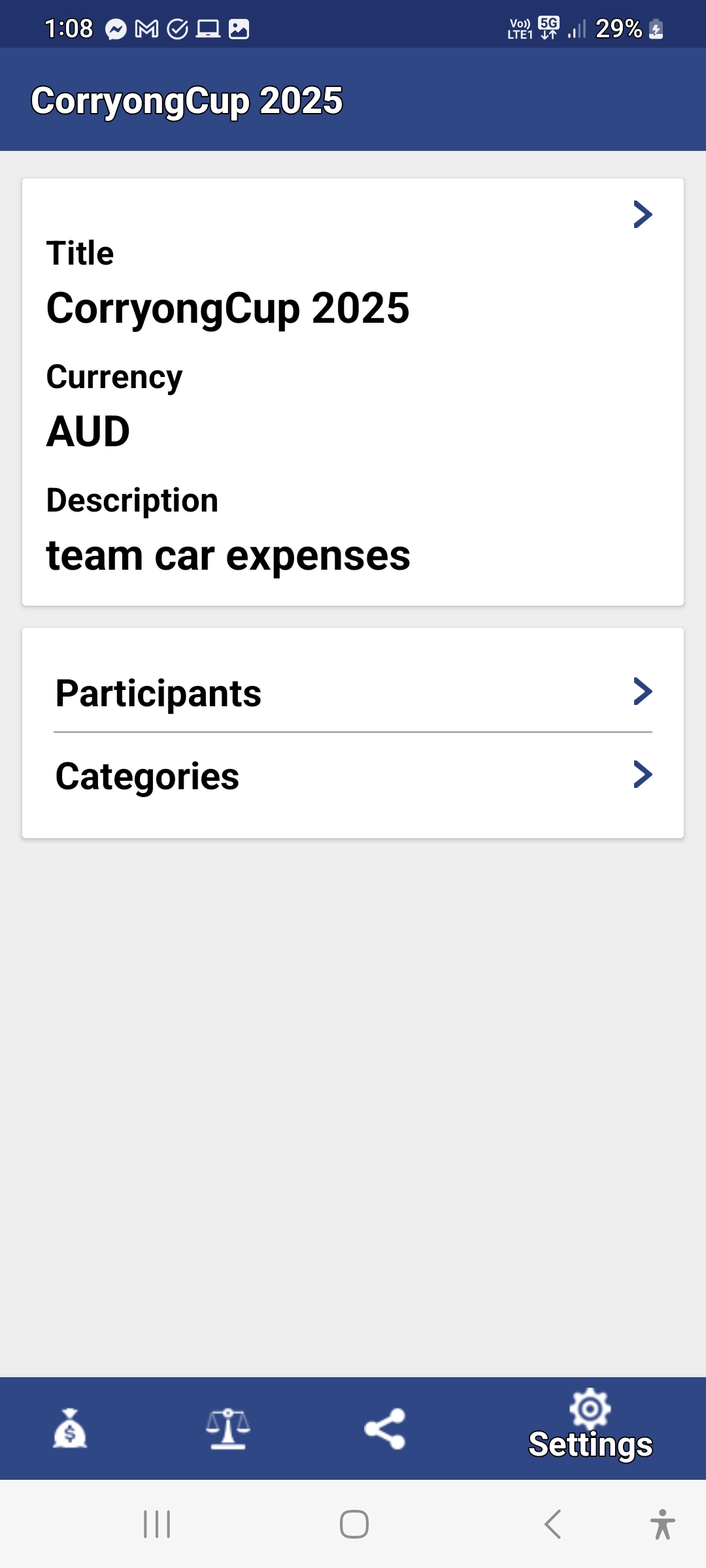

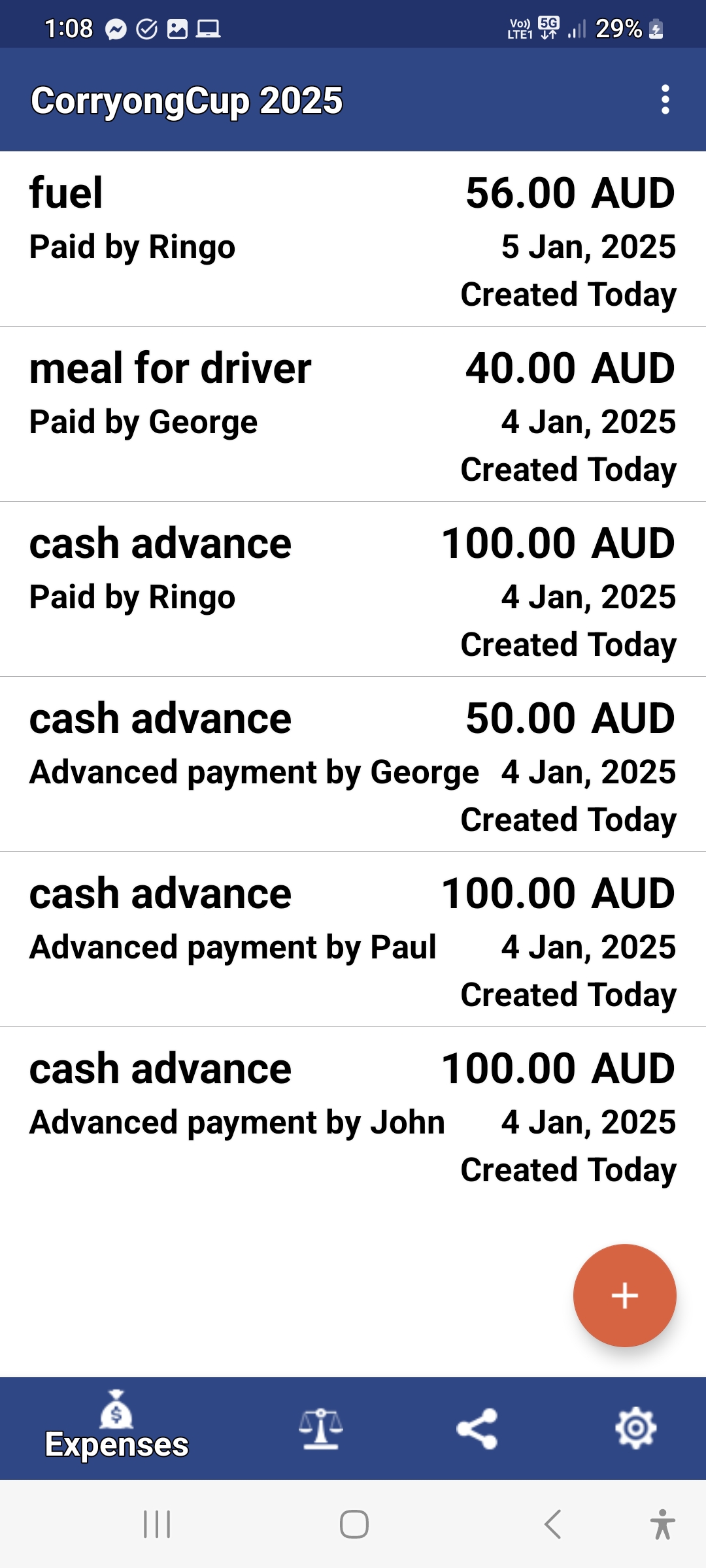

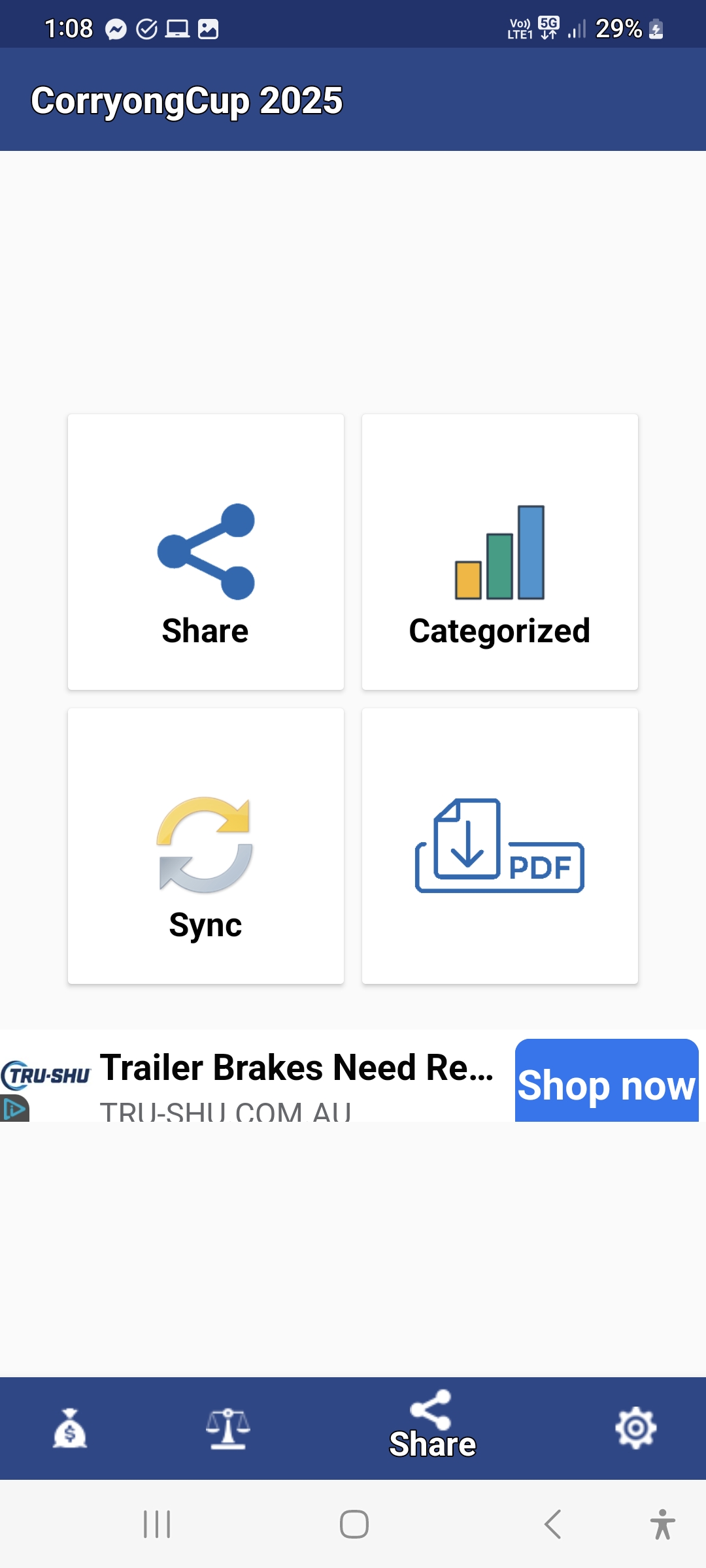

I have recently found an free app that appears suitable for sharing vehicle expenses. Group Xpense

It supports syncing data between different group devices so everyone on your team can have the app installed and record expenses. The data is shared across your group.

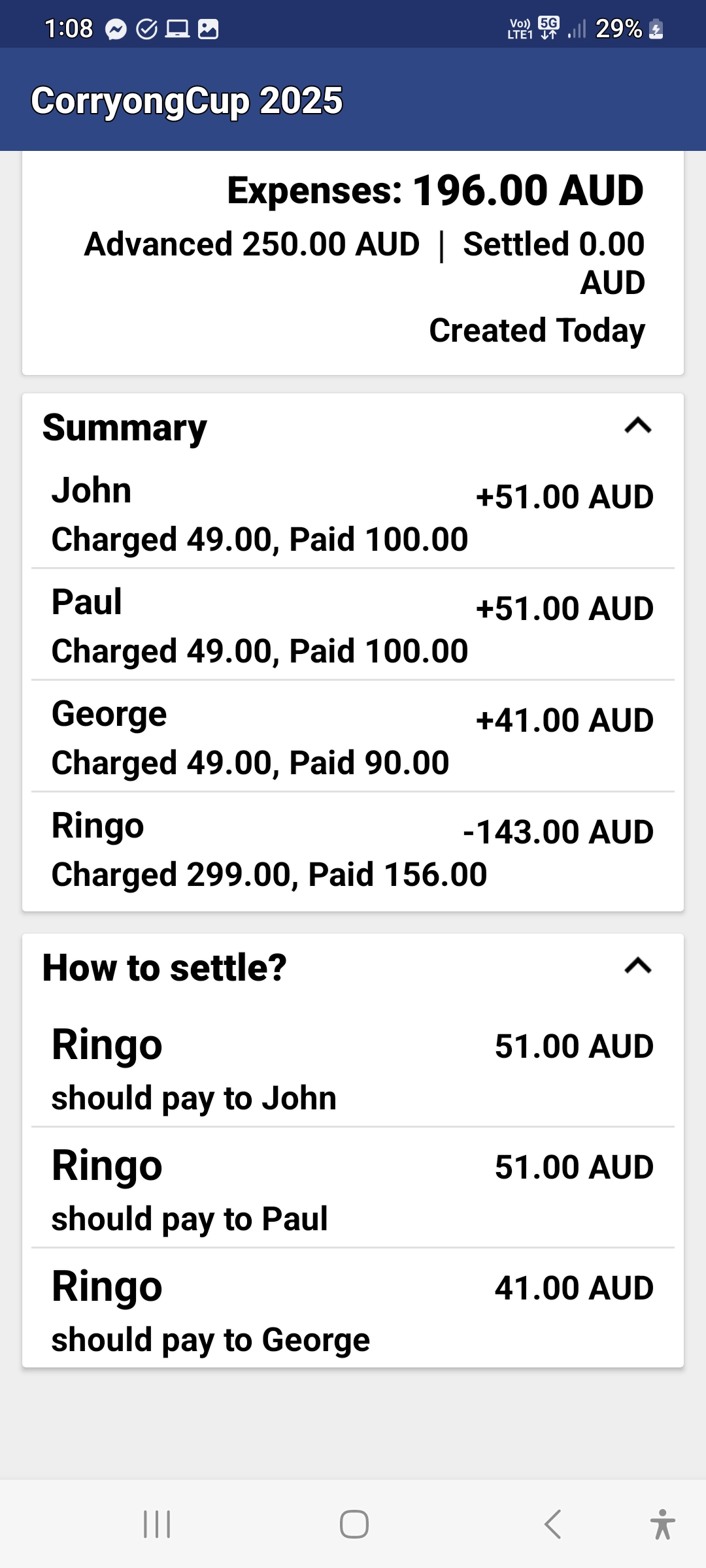

In the scenario below all pilots paid a cash advance to the vehicle kitty held by Ringo.

After the first day of flying there are total expenses of $196 split 4 ways, $49 each.

Ringo's charged balance is higher because he is holding the $250 paid to him by John, Paul & George.

If you want to use the $1 per km travelled method then fuel is not a shared expense and add an expense at the end of the comp. for distance travelled by the vehicle.

Be prepared before you go to a competition. Ensure all of your gear is ready.

- Glider and harness in airworthy condition.

- parachute freshly repacked

- zips & slides all lubricated & operational

- radio, headset & switchbox all functional

- team car in reliable working condition

- Tow gear (gauge, rope, rope winder, tow bridle, weak links) all serviceable

Everything you need to fly should fit into 2 bags. Your glider bag and your harness bag. If your basebar wont fit in your glider bag because of your wheels then get removable wheels. You don't want to hold-up your team going back to get forgotten gear.

Your team car should have a tool box but there isn't room in the retrieve car for everyone to bring their own, that would be encroaching on Eski space.

Having gear that is reliable will inspire confidence and reduce your mental workload while setting-up and while flying.